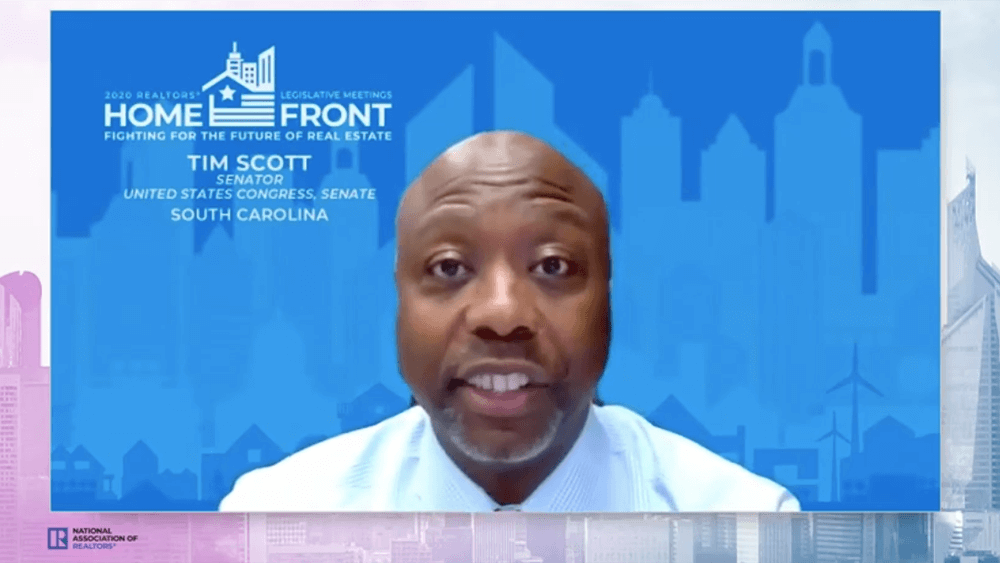

U.S. Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina addresses the online audience for the virtual REALTORS® Legislative Meetings & Trade Expo.

In March, like many other event organizers, Bonnie Stetz, director of conference content design for the National Association of REALTORS® (NAR), found herself in the position of having to convert a live event to virtual in a very short period of time — five-and-a-half weeks, to be exact.

There was no chance that the event — REALTORS® Legislative Meetings & Trade Expo, scheduled for May in Washington, D.C. — could be postponed or canceled, Stetz said. In fact, the pandemic made the timing of the event even more critical. The speakers that had been invited to the meeting “are heavyweights with the CARES Act,” she said, “and all of our members are entrepreneurs and independent contractors and small business owners.”

The event is held each year over six days in D.C. and includes briefings for participants “on the talking points that are relevant to their areas and the legislation that’s up so that they can meet with their representative on behalf of the real estate industry,” Stetz said. This year, the legislative meetings would be “related to the PPP and the SBA loans and everything about the CARES Act, so we still needed to have this meeting over the same dates.”

Bonnie Stetz

While the physical event wasn’t feasible, the prospect of moving it online was especially daunting: Aside from professional development webinars, NAR had never done anything virtual in the “conference arena,” Stetz said.

Choosing the Right Platform

NAR’s legislative meeting typically attracts 10,000 attendees, and is free to attend, but Stetz knew that number could easily multiply with an online version. “My understanding is that once you add a hybrid piece or you go virtual completely, you should expect a 30-percent bump in attendance,” she said.

NAR chose to purchase an enterprise-level Zoom license in addition to using Freeman Online Event Pro for the streaming platform to support the audience numbers. “We thought we would get around 15,000-20,000 attendees, and we ended up with 28,000,” she said. “But the whole time we were load testing the system for 30,000, so we were prepared for the amount of traffic that we got. It is really important to make sure that your vendor and you are prepared for a much higher load than you would ever anticipate having.”

Instead of being a six-day event, the online event was spread out over 15 days with 126 business, committee meetings, forums, and education. Virtual committee meetings took place April 27–May 15 and virtual conference sessions May 12–14.

Speaker Contracts

One area Stetz knew that they had to address right away was their speaker contracts. Former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and former Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel were scheduled to speak at the face-to-face event and Stetz and her team reached out to their speaker bureaus and were assured that their contracts covered online presentations. “We received confirmation that both speakers were willing to speak virtually on the same date we had previously planned. We never got an addendum from them, and so we figured we were good,” Stetz said. That is, until the day before the virtual event, when the bureaus told them that they would not be able to broadcast their talks to Facebook Live and YouTube — both talks had been promoted extensively as being on those platforms.

NAR reached a last-minute compromise with the bureau and with Christie and Emanuel that they would be broadcast to Facebook Live, but their talks would be taken down immediately after they spoke, and only available via password for a limited time.

Zoom Security

The other challenge was that “the representatives on the Hill had already experienced Zoom bombings” at other online events, so they told NAR that they preferred to send in pre-recorded videos, Stetz said. Others wanted to call in and not be on video. “So we had to do this whole awareness campaign and write up security protocols, and figure out all the best ways to make sure that we would not be Zoom bombed so that we could convince all of these speakers that we were supposed to have from the government to actually still speak to us and to our members live,” she said. “We tested a bunch of different things.” One simple step was to not mention Zoom in any promotions or on NAR’s website. “We also had an exit strategy in case something happened,” Stetz said, “but we didn’t have to use it. We had 126 meetings and we never got Zoom bombed.”

For the main nine talks that were broadcast, Stetz’s team got the speakers “into a waiting room, a green room, and then we put them in Zoom rooms by themselves where the production was streamed from,” she said. “They weren’t even given a link directly to the room they would be in, they went into a green room first and then we moved them in there.”

Training

Stetz said that she and her team spent a great deal of time and effort in making sure that Zoom’s different capabilities were leveraged for each type of event. For instance, the board of directors meeting was held using a “two Zoom meeting combo-type deal,” she said, “where we had one Zoom webinar product that had the people who are allowed to vote. And then the other product was just the observation gallery — or a separate Zoom meeting that we streamed into. So Zoom A was the voting meetings, the voters, and then Zoom B was the observers.”

Stetz and her team also sent speakers guidelines for best practices for virtual presentations, “so that ahead of time they could make sure they had the bandwidth and the integrity in their connection once they were speaking. We got really lucky with that — we didn’t have any problems with any of our speakers losing their video or losing their audio.”

Stetz said they “struggled with virtual backgrounds. They’re very popular right now, but they also take up bandwidth. And a lot of computers, older computers, don’t display them correctly or can’t display them at all. Your lighting has to be right, your background has to be right. You can disappear, they can become a distraction. So we ended up having branded backgrounds, but if they didn’t look good, we wanted people to be prepared to have a natural background.”

Realtor, author, and podcast host Brian Buffini presents his session, “Business Strategies That Meet the Moment,” at the virtual REALTORS® Legislative Meetings & Trade Expo.

Prepare and Envision

Essential to the success of NAR’s first virtual event was its process of journey mapping, Stetz said. “That helped us a lot, to try to visualize the experience each role would have, like what is the chair going to experience from the time that they register to the time they finish their experience? And what’s the participant experience? Like, they’re going to click this button. They’re going to see this. They’re going to wonder about this. That was huge.”

In addition, Stetz and her team trained “helper staff” — non-IT staff — on Zoom. Their job, for instance, would be to sit in on a meeting “so that the person who was running the meeting could attend to their chair, and then this extra staff person was there for support,” she said.

Going forward, Stetz said she expects there is going to be a stronger demand for virtual and hybrid events — and if there’s one thing her crash course has taught her is that planning for the digital experience requires more resources than you might think. “When you’re adding a virtual event to a live event, it becomes an entire other event,” she said. “You have to talk about staff resources and budget. Whatever the level of your live event is, you have to be able to step up to that with whatever virtual offerings you have in order to make sure the value proposition is still there.”