The meetings team at Association Headquarters disrupted the traditional classroom-style experience at the 2013 winter meeting of the American Society of Transplantation by, among other ideas, decreasing the distance between the speakers and the audience.

It’s not easy to change a meeting that’s been done the same way for many years — much less a learning paradigm that’s been in place since the 13th century. That’s how long we’ve been putting learners in rooms, seated in rows and columns, with the expert up at the front, bestowing knowledge, Lennie Scott-Webber, director of education environments at Steelcase Inc., said during a breakout session at PCMA Convening Leaders 2013 in Orlando last January. We’re so conditioned to expect the traditional kind of learning environment, Scott-Webber said, that it’s hard to break the mold — even though research shows that we retain only 5 percent of information presented in that setting. In comparison, we retain approximately 85 percent of the information we encounter when we learn interactively.

Tina Squillante

As Scott-Webber shared research about adult learning and the impact of the meeting environment on education, Tina Squillante, CMP, sat in the audience, scribbling notes and making connections between what she was hearing and the programs that she plans as director of meetings, exhibits, and special events at Association Headquarters, based outside Philadelphia, in Mt. Laurel, N.J. “More and more, studies about the way that people learn show that it’s not just about being a passive learner,” Squillante said in a recent interview with Convene. “If learners learn more by interacting, rather than by just reading information, and [if they learn more] by having more engagement and conversation, either with a co-attendee or by being able to speak with the speaker more freely, then I want to give them that opportunity.”

Those two themes — how interactivity improves learning, and the impact that environment has on learning behavior — kept repeating themselves during Convening Leaders 2013. And as ideas accumulated, a vision for radically changing an upcoming meeting took shape in Squillante’s mind.

At the time, the 2013 winter meeting of the American Society of Transplantation (AST), a longtime Association Headquarters client whose members include transplant physicians, surgeons, and scientists, was almost exactly one month away. Over the years, Squillante had tried to change up the programming for the 325-attendee event, she said, by introducing “new ways of interacting and learning.” But still, it was “kind of a boring and dying meeting,” she said. “It needed an overhaul.”

“When I started listening to the sessions [at Convening Leaders],” Squillante said, “I pulled my meetings manager [Kristin Brammell Burke] over, along with my PSAV rep [Roy Golden].” Squillante pointed out that AST recently had changed the winter meeting’s name to CEOT, for Cutting Edge of Transplantation. “This just opened up the door for me to say, ‘We can do this differently — and we should,’” she recalled. “I said, ‘Okay, you guys, this is what I want to do. I drew them a picture. We are going to make this a cutting-edge meeting.’”

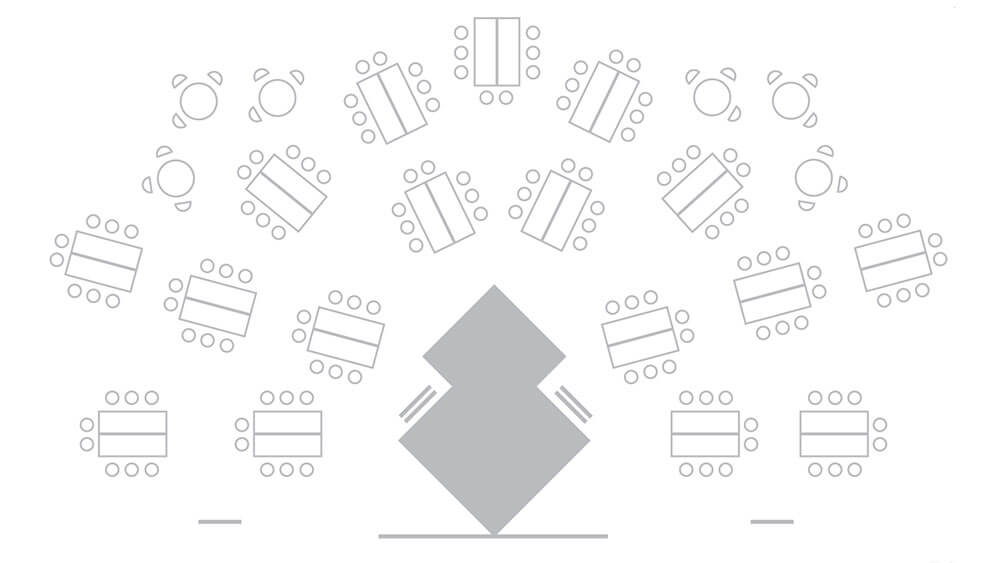

The room set for the American Society of Transplantation winter meeting (CEOT) went through several rounds of sketches.

Setting the Stage

Squillante eventually would identify 10 key elements in her plan to reinvent AST’s meeting. But one of the most basic challenges was to remove, as much as possible, the barriers between presenters and the audience — to get rid, she said, of the “talking head.”

In a Convening Leaders 2013 session called “Improve Your Learning Environments Today,” Kimberly Lewis, vice president of community advancement and conferences and events for the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), had demonstrated one interesting way to shift that dynamic. At a recent Greenbuild program, USGBC’s annual meeting, speakers were placed in the middle of a room, on a round stage flanked by large screens, surrounded on all sides by attendees. But as much as Squillante liked the idea of 360-degree seating, “I knew my guys couldn’t do that,” she said. “They wouldn’t feel comfortable.” She instead proposed a modified plan for CEOT: putting attendees on three sides of the stage, with the speaker in the center.

And although she wanted to use a round stage like the one at Greenbuild, a custom stage wasn’t in her budget. In fact, her budget pretty much limited her to using the existing rectangular risers at the meeting hotel, the Sheraton Wild Horse Pass Resort & Spa, in Chandler, Ariz.

It was a challenge that Squillante solved — ingeniously — by using the risers to create a diamond-shaped stage, which was pushed away from the back wall and extended out into the audience. Configuring the stage on a diagonal “allowed me to put seating on two sides as well as the front,” Squillante said. And “I kept [the stage] as low as it could go,” further reducing the space between audience and speaker. She took away the lectern, but eased the transition for CEOT’s speakers by adding a small cocktail round on stage.

Squillante also placed three large video screens in the room — up front and in two corners — so attendees could be relieved of the need to keep their eyes trained on the presenter on stage. (“If you can move,” Scott-Webber had said, “you can learn.”) She added two smaller screens at the sides of the stage. “That’s for the person who needs to shift in their seat and needs to wander — who is listening with one ear, but not necessarily staring at the presenter,” she said. “They can still see a screen somewhere else.”

For CEOT 2013, Tina Squillante and her team placed three large video screens in the room so attendees could be relieved of the need to keep their eyes trained on the presenter on stage.

Rounds, Pods, Rows

Choice also was a key factor as Squillante planned what she called “personalized” seating at CEOT 2013. “A lot of the sessions [at Convening Leaders] talked about giving people seating options,” she said. “I wanted to give people a choice of where they sat, how that sat, who they sat with, or to sit alone.”

Choice also was a key factor as Squillante planned what she called “personalized” seating at CEOT 2013. “A lot of the sessions [at Convening Leaders] talked about giving people seating options,” she said. “I wanted to give people a choice of where they sat, how that sat, who they sat with, or to sit alone.”

Squillante also wanted to encourage networking between attendees as much as possible. “I wanted to give people the option to sit with a small group of friends, or with people they didn’t know, to perhaps meet new people in the field,” she said. “[When attendees] are just chitchatting, sometimes they start talking about the research they’re doing. They might be working on very similar projects…. You never know when collaboration might happen.”

Her plan included small cocktail rounds in the meeting room, “for people who might be coming with their colleagues,” she said. She added rectangular tables seating six to eight, for bigger groups and as places where people who didn’t know one another could sit comfortably but still easily converse. “A crescent round, to me, has too much space,” she said. “You could sit there and still not talk to other people.”

Squillante also knew from experience that a certain number of attendees like to stand in the back of the room. “They fidget or they want to get up and down,” she said. “They just want to be able to get in and out of the room easily.” For them, she added rows of theater seating. “I know they’re going to [want to be in the back],” she said. “So let’s accommodate them.”

Squillante initially had planned to add couches in front of the stage, but thought better of it. CEOT is highly technical, and speakers sometimes might be talking about something that attendees aren’t 100-percent interested in. “I don’t want to see anyone dozing off,” Squillante said. “I don’t want them that comfortable — I drew the line there.”

Putting the Pieces Together

At CEOT 2013, which was held on Feb. 13-16, the changes in the room setup helped speakers break out of their longstanding patterns, just as Squillante had hoped. “Speakers were actually speaking to the people all around them,” she said. “They were talking, moving, and walking. The speakers were engaging [attendees] more, because they were right there with them, in the middle of the audience. It was amazing.”

USGBC’s Lewis had warned her audience at Convening Leaders that not every speaker would embrace a new environment. But for the most part, CEOT’s speakers “loved it,” Squillante said. One of the tips she brought back from Convening Leaders was to acclimate speakers to the new environment in advance. She invited them to “come to the room, get up on the stage, and play with the technology,” Squillante said. “They could really get comfortable in the space.” Not every speaker took her up on the offer, she said, but “the ones that did, I physically took them with me and got them on the stage. I made them walk around.”

It seems to have paid off. During some presentations, speakers were so comfortable that they began illustrating their points not by reading from their PowerPoint slides but by calling out to relevant experts in the audience. “They were saying, ‘Hey, Joe, I know you do this,’” Squillante said.

Squillante also had coached session moderators in advance to be conversational. “I don’t want you doing Q&A from a head table,” she told them. “I want you to get on the stage and to join the speaker and have a conversation. Let them take your questions, but have a dialogue with them.” The change in style changed the dynamic of the whole room, she said. “It gave people permission to engage the speaker.”

Making it Interactive

Another way that CEOT 2013 added interactivity to the meeting was through polling. At the beginning of every session, moderators led attendees through a handful of questions, which were repeated at the end. Squillante used Poll Everywhere, an audience-response platform that attendees access via smartphone. “It’s very inexpensive,” she said. “You could get more sophisticated systems. My budget is my budget, and this works. And it allowed people to pay attention, to be engaged, and to do something physically.”

Another way that CEOT 2013 added interactivity to the meeting was through polling. At the beginning of every session, moderators led attendees through a handful of questions, which were repeated at the end. Squillante used Poll Everywhere, an audience-response platform that attendees access via smartphone. “It’s very inexpensive,” she said. “You could get more sophisticated systems. My budget is my budget, and this works. And it allowed people to pay attention, to be engaged, and to do something physically.”

Tina Squillante and her team replaced table-top trade show exhibits with video kiosks, making the 2013 CEOT more interactive for attendees.

Polling “wakes up attendees,” she said, but at CEOT 2013 it also was a way of collecting information about the impact that speakers had on attendee knowledge. “We didn’t show what the change was during each session, but we brought that data back with us, and it was analyzed after the meeting.”

Another goal was to enhance the room, as much as possible, in away that stimulated attendees’ attention and emotions. To do that, Squillante used high-tech movable lights that could project an almost unlimited range of colors and textures onto the meeting-room walls. Squillante had worked with colored lighting at her events before, she said, “but this takes anything I did before times 10.”

The intention was to enrich the environment without being distracting, so any changes in the lighting occurred as attendees were out of the room for meals or breaks, for the most part. Squillante said she knew the lighting was working to refresh the environment when a presenter who was standing next to her asked her if she had moved the room’s furniture around during a break. “I looked at him and I said, ‘Well, not really,’” she said. “‘I did change the lights.’”

The changes in color were based mainly on intuition — colors got brighter as the day wore on and energy lagged, with one exception. At Convening Leaders, Lewis talked about “biophilia,” the hypothesis that there is an instinctive bond between humans and other living systems, and that we’re more receptive and comfortable when surrounded by nature. So Squillante made sure that one of the textures she repeated was from the natural world. Her budget didn’t allow her to fill the room with rented plants, she said. “But I could [project] green palm leaves up on my wall.”

Knowing What Works for You

Squillante left Convening Leaders 2013 with “a huge list of ideas of what we could do and what we could implement,” she said. But knowing how to edit and adapt such a list to fit your own circumstances is key. “You have to know your group,” Squillante said. “You have to know what will work and what won’t. What’s the baby step you could get away with? You can’t do something that’s going to take attendees completely outside their comfort zones. It will flop. You have to know your meeting.

Another takeaway for Squillante was an indirect one: Believe in yourself and your ideas. Early in the planning of CEOT 2013, an AST program chair had asked Squillante to drop the meeting’s tabletop trade-show-style exhibits because they didn’t represent how AST members prefer to get information. “If I want to find out about something,” the program chair told her, “I’m either going to go to the company’s website or I’m going to call my rep and have a conversation about it.”

Squillante initially resisted getting rid of exhibits, both because there were sponsors who wanted to be at the meeting and because they generated income. But she came up with an alternative: technology-enabled kiosks, where exhibitors could present product videos. When Squillante talked about the kiosks at Convening Leaders last year, other attendees were anything but encouraging. “They told me it wasn’t a good idea,” Squillante said. “They pooh-poohed it.” But in fact, the kiosks were a big success at CEOT 2013. For as much as people said they would never work, “we made a lot of money.”

For Squillante, the lesson was this: “Believe in what you know. If you know your group and you have an idea, try it. Take a risk. Take baby steps. Take the risk and just try it.”

The immediate result of the risks that Squillante took at CEOT 2013 was a flood of rave reviews. “I’ve been in the transplantation field over 20 years and have been going to meetings for just as long,” one attendee wrote. “This is the best meeting I have ever been to.”

Squillante gives much of the credit for the meeting’s success to AST itself, and the effort that the organization made to bring cutting-edge education to its members. “People came because they knew there was going to be a great program,” she said. “Then they had this unbelievable experience. The combination made a huge difference.”

The type of experimentation that Squillante incorporated into CEOT 2013 is also part of a larger shift that will last beyond the success of an individual meeting — an exercise in using what’s known about how people learn to make live programs more effective. Indeed, Squillante noted, research is changing how education is delivered throughout our educational system, including in colleges and universities. “That must flow into a medical meeting — or any meeting,” she said. “If it’s proven that this is a better way to learn, then why not make it available at your meeting, where you want people to learn the most up-to-date information in their field?”

“At its core, creative confidence is about believing in your ability to create change in the world around you,” brothers David and Tom Kelley write in Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All.

Cultivating Creative Confidence

In Tina Squillante’s Education Day presentation for the PCMA Greater Philadelphia Chapter last September, she shared in detail the steps she took to turn ideas into reality as she resuscitated a fading medical meeting. But she also gave her audience of colleagues a look into how she thinks about her role as a meeting planner and what it takes to be innovative.

“Everyone in this room is creative or you probably couldn’t be in this field,” Squillante told the audience. “And every planner holds a lot of power — believe it or not. Sometimes we have to speak up and say what we feel, believe in, what we know in our gut will make an experience better for our attendees.”

Squillante’s mindset could be described as having “creative confidence,” which is also the title of a new book about creativity and innovation by David and Tom Kelley, brothers who are the founder and a partner, respectively, of IDEO, one of the world’s leading design firms. “At its core, creative confidence is about believing in your ability to create change in the world around you,” the Kelleys write in Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All. “We think this self-assurance, this belief in your creative capacity, lies at the heart of innovation.”

Striking Resemblance

If you compare Squillante’s description of how she implemented change at the American Society of Transplantation’s (AST) 2013 winter meeting to the Kelleys’ book, it’s striking how closely her actions align with their insights and recommendations. For example, successful innovation, the Kelleys write in Creative Confidence, balances three things: technical feasibility, business viability, and human factors.

Technology has to be more than cool, they write — it has to work. To that end, Squillante said she has “great support” from the AV consultant she works with. That expert can be “your best partner for medical meetings.”

Even in nonprofits, the Kelleys write, “business factors are critical.” Indeed, staying within budget was a key element in Squillante’s plan. Virtually every idea she implemented adapted to group and budget.

For example, one source of inspiration for Squillante’s room setup was a round stage used at the U.S. Green Building Council’s Greenbuild conference. But while investing in a custom stage makes sense for a meeting with 35,000 attendees, like Greenbuild, it didn’t fit the budget for a meeting for 325, which was the size of AST’s meeting. But rather than giving up on the idea, she found a way to adapt the concept with the materials that she could afford: standard risers placed together to create a diamond shape.

Squillante spent a little bit on lighting for the room, but she balanced the cost by using inexpensive polling software. “You rob Peter to pay Paul,” she said. “And if someone looks at this and says, ‘I can’t afford it,’ I’d say, ‘Yes, you can.’ You can use light trees.” Another inexpensive option, Squillante said, is to use LCD bar lights, placed on the floor, as uplighting.

As for the human factor, the Kelleys define that as “deeply understanding human needs” — which, they write, “aren’t necessarily more important than the other two. But technical factors are well taught in science and engineering programs around the world, and companies everywhere focus energy on the business factors. So we believe the human factors may offer some of the best opportunities for innovation, which is why we always start there.”

Squillante also started the reinvention process with human factors as her foremost concern. “The reason people join societies is for education and networking, right?” she said. “To me, it’s up to the planner – it’s our responsibility to create the best learning environments possible.”

And while networking may be a top reason why people attend meetings, not everyone comes with the same personality, contacts, or ability to connect. Squillante had observed attendee behavior and sought to support a variety of preferences, with seating options that allowed attendees to talk one-on-one, to comfortably meet new people in groups, or to sit alone. And instead of trying to change the behavior of meeting attendees who dashed in and out during sessions, she accepted and accommodated it.

A Word About Constraint

Squillante launched an overhaul of AST’s meeting when it was just a month away, without extra money budgeted for enhancing the event. While it may seem like more time and more money are always good things, that isn’t always the case.

“Although ‘creative constraint’ sounds like an oxymoron, one way to spark creative action is to constrain it,” the Kelleys write. “Given a choice, most of us would of course prefer a little more budget, a little more staff, and a little more time. But constraints can spur creativity and incite action, as long as you have the confidence to embrace them.”

A Creative Support Network

PCMA Convening Leaders 2013 was a wellspring of ideas for Squillante, which she implemented by working with her team — all “rock stars,” she said. And according to the Kelleys, “when a group embraces the concept of building on the ideas of others, it can unleash all kinds of creative energy.”

They write: “Creative people are often portrayed as lone geniuses or rugged individuals. But we’ve found that many of our best ideas result from collaborating with other people. From make-a-thons to multidisciplinary teams, we treat creativity as a team sport. Like many elements of creative confidence, building on the ideas of others requires humility. You have to first acknowledge — at least to yourself – that you don’t have all the answers. The upside is that it takes some pressure off you to know you don’t have to generate ideas all on your own.

”… Even if you haven’t found the right collaborators yet, you too can build on the ideas of others. Check out creative digital communities. Form an all-volunteer project team that works after hours on an idea that’s important to you. Spearhead a creative confidence group that meets once a month for lunch or for drinks after work. In other words, take action to build your own supportive community of innovators.”