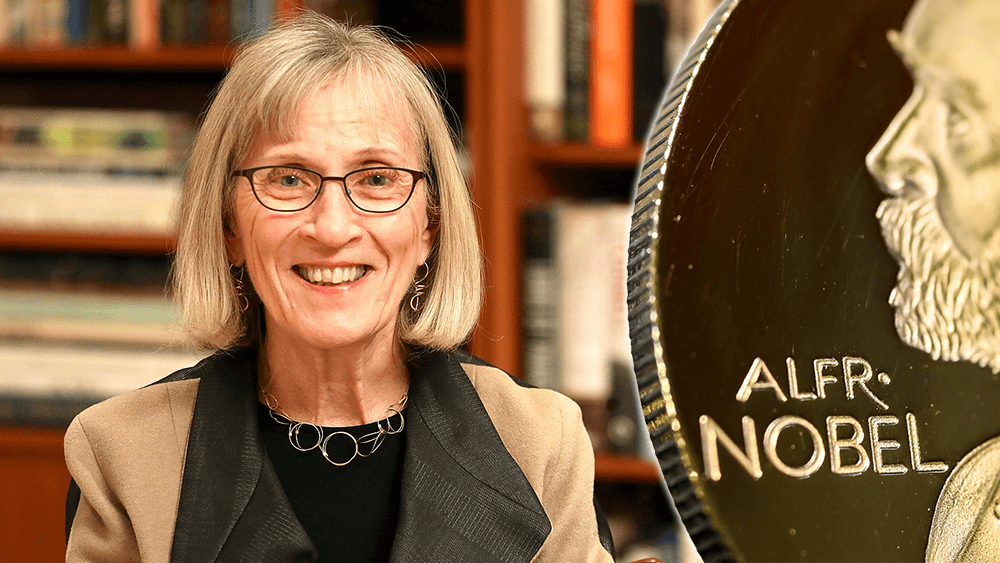

Claudia Goldin, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard University, was the third woman to be awarded the Nobel economics prize — 93 economics laureates have been male. (Editing 1088 Photo)

Harvard University professor Claudia Goldin was awarded the Nobel economics prize Oct. 9 for her research into what is driving the gender pay gap — women are now better educated, on average, than males, yet in the U.S., they make a little more than 80 cents for every dollar a man makes.

Goldin’s research has traced the contemporary gender pay gap to what she calls “greedy work” — the kind of jobs that demand long hours and around-the-clock availability. Most caregiving responsibilities still disproportionately fall on women, and many working mothers opt to take jobs with higher flexibility and lower pay, Goldin told Harvard Business Review.

Over the last two centuries, gender wage gaps could be explained by differences in education and occupation, but “the bulk of this earnings difference is now between men and women in the same occupation,” the Royal Swedish Academy wrote in awarding the Nobel Prize to Goldin, “and it largely arises with the birth of the first child.”

One of the results of Goldin’s research is that it challenges the arguments that men earn more than women simply because women prefer different kinds of occupations or that wage gaps can be explained solely by discrimination. According to her research, women with children often work in firms or for institutions that demand less of their time.

Child-care shortages during the pandemic put even more strain on working mothers. U.S. women had the highest participation in the labor force in the 1990s, but are now less likely to work than their counterparts in France, Canada, or Japan, Goldin told Associated Press. “When I look at the numbers, I think something has happened in America,” Goldin said. “We have to ask why that’s the case. … We have to step back and ask questions about piecing together the family, the home, together with the marketplace and employment.’’

What About the Business Events Industry?

What could that mean for the events industry, where an estimated 77 percent are women and, on average, are out-earned by men?

One thing conference organizers can do to help level the playing field in the sectors they serve is to remove hurdles for participants and speakers by providing child care at their events. They also can offer online events as a way to include more participation by women — two separate studies revealed that online events held during the pandemic resulted in increased participation among women as both attendees and speakers, compared to their in-person, pre-pandemic versions.

Overall, employers can look at offering flexibility to their employees — not just as a benefit for them, but an economic advantage to their companies, as a way of retaining talented women who might otherwise leave jobs in order to meet caregiving responsibilities. In 2021, the cost of women exiting the workforce lowered the GDP by $97 billion.

For many workers, the pandemic’s silver lining has been an increase in flexible and hybrid work environments. In the 2019 Salary Survey, conducted before the pandemic, only 14 percent worked from home full-time, and one-third worked from home part-time. In this survey, 88 percent reported working for employers with a flexible work policy.

And while no direct relationship can be drawn from our surveys on the effect of work flexibility on pay, it is worth noting that between the 2020 and 2023 surveys — the same period that saw a massive growth in flexible work — the gap between male and female pay also closed significantly: In the 2020 survey, women averaged $14,000 less than their male counterparts; in the 2023 survey, men out-earned women by less than $5,000.

The growth in flexible schedules doesn’t mean that meeting professionals are working less intensely or for fewer hours — half of this year’s survey respondents said they worked between 41 and 50 hours a week and 16 percent regularly worked 51-60 hours a week. More than three-quarters of planners said they had more responsibilities added to their job description in 2023, compared to 67 percent who said the same in 2020. But when respondents were asked to list what they liked best about their jobs in an open-ended question, among the most highly valued aspects — as Goldin’s research also showed — was flexibility.

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor of Convene.