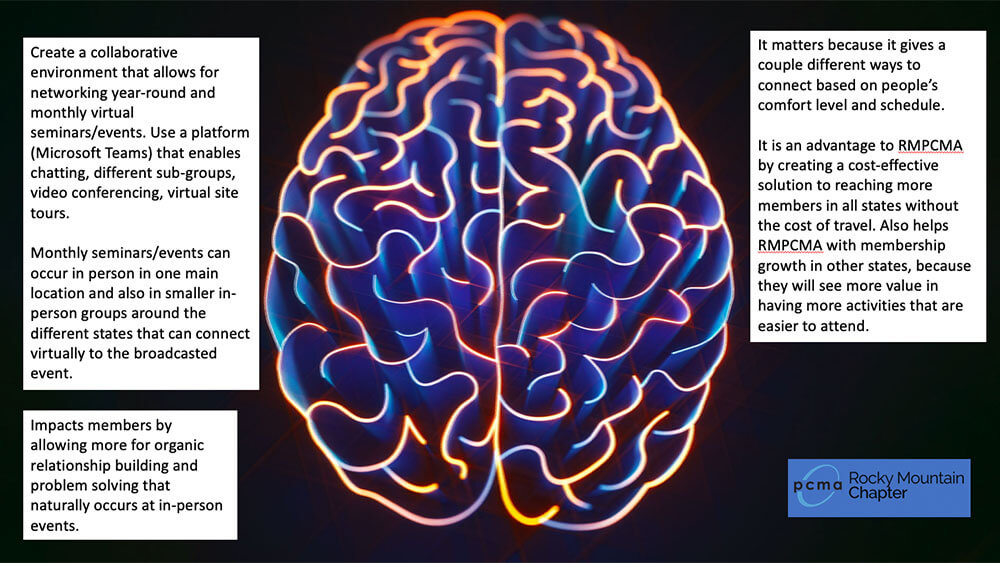

The Utah Valley Convention Center group in Provo was the winner of the Rocky Mountain Reskill Roadtrip hackathon. They came up with the suggestion to use a platform like Microsoft Teams to enable chatting, sub-group channels, video conferencing, and virtual site tours as a way to network and engage year-round.

“Remember the carefree excitement of a road trip with your friends with no idea where you’re headed or what you’ll encounter along the way? Our industry just hopped into the van together, headed down the highway into the great unknown again. … But this time, the stakes are higher, the uncertainty is overwhelming and we must be very intentional about what we bring with us and what we leave behind.”

So begins the overview of R3: The Rocky Mountain Reskill Roadtrip, setting the tone for a hybrid/hackathon event organized by the PCMA Rocky Mountain Chapter and held on April 8, Global Meetings Industry Day.

Daniel Stones

R3 was something of a meta event — the hackathon portion of the program was intended to solve the challenge of engaging chapter participants in hybrid channels year-round while online and in-person participants were themselves trying to bridge the digital divide. Daniel Stones, CMP, DES, director of programs for the PCMA Rocky Mountain Chapter, and webinar production manager at MGMA recently filled Convene in on how the event came together.

What were the goals of R3?

We’ve been very focused at the chapter on how do we retrain for this unknown future? We’ve pursued that very passionately — how are we getting back to business and how can we make events happen? [Instead of] standing still, we’re really trying to chase down some viable solutions that people can take home. And so that was really at the heart of R-3.

It offered people a great chance to get their hands dirty and learn from our mistakes, to try new things so that you can get experienced with it. And so that was really the goal here.

We had one primary location where we broadcast from the presentations and stuff like that, but the event was designed to operate as a regional hybrid rather than a hub-and-spoke model. So to differentiate between those two, each location was able to receive broadcasts from all of the other locations and was able to broadcast out to all of the other locations. We had four physical locations in three states — the Hilton City Center and the JW Marriott Cherry Creek in Denver; the Little America Resort and Casino in Cheyenne, Wyoming; and the Utah Valley Convention Center in Provo, Utah. And then we had the option to participate virtually from home. The initial plan was to have a venue in Albuquerque as well, but the New Mexico state regulations were too restrictive for that — we were not allowed to have any in-person event.

Were there differences in regulations between the three states?

Yeah, there were. And the status changed over time, too. So throughout this planning process, at one point everything was much more restrictive. And then we got into vaccines and some locations started to open up a lot more. And then obviously Albuquerque just was not allowed to do it. But we were still able to say, “Hey, if you’re from Albuquerque, join us for the virtual side. Be one of our virtual groups and you can still participate in the hackathon and still be eligible and to do the work and win the prize.”

It gave us some great contingency plan options. We had plans to scale up or scale down as needed, as the situation warranted.

How many were you allowed to have in person in Denver?

In the end, we really didn’t have capacity in either of the Denver venues that would impact us. That was nice in that we had free rein, but not nice in that we didn’t have enough attendees to test that capacity.

Did you have more attendees digitally than you expected?

No, actually I would say I have fewer virtual attendees. We had some troubles with the ramp-up to launch — it was a bit of a challenge on our side. There were a lot of staffing changes and with the website development side and we launched our marketing a little bit later than we would have liked to. So we had fewer virtual attendees than I would have originally expected, but then again, I think that the ones who really wanted to participate were gung-ho about getting back to being in person.

What was your goal with the hackathon program?

Their task/problem to solve was to come up with their own hybrid engagement tool that we can use throughout the year to connect across state lines because we’ve struggled for years to try to bridge that gap between Denver and all of our other states, like New Mexico and Utah, Wyoming, and really pull those planners in as well.

The hackathon was the majority of the programming, but there were also some other critical pieces that we had to work in. One was the Global Meetings Industry Day that Meetings Mean Business was putting on.

Cogent Global Solutions was our streaming partner and we used same the virtual platform, Hubilo, that they use. Behind the scenes, the streaming platform was Zoom, but it doesn’t look exactly like a Zoom room. Each location had their own private room in the platform. Cheyenne had the Cheyenne room and then we could actually control who could get into that room and who couldn’t. So then that way, our mentors or judges who needed to go in and talk to the groups on occasion could hop into that room from wherever they were and chat one-on-one with the group that’s in Cheyenne and then just go to the next Zoom room and talk to the next group.

So the Cheyenne group is there in-person, working on coming up with a tool for the hackathon. And then there’s a virtual group that’s also working on the challenge. Were they talking to the in-person group? How did that work?

Well, the answer for this event was all of the above. There’s a reason you’re having trouble getting it straight because as the planner, I had difficulty getting it straight. There were a lot of moving pieces, but we had our virtual group, and they could all go in from their room and form a group in the virtual platform. And then you’ve got the same thing, just like in Cheyenne, it’s just not a whole bunch of people individually logging into that room via the platform, they’re just hanging out.

And their AV is connected into the Cheyenne breakout room on the virtual platform. And so then that way our mentors could hop in on basically a little Zoom call with any of these groups. If they’re looking into the Cheyenne group and you can see all of them sitting around a table in here. And so we’re just on the Zoom call by ourselves until you hop in and so from your spot, you’re just like, “Okay. Time for me to check in on the Cheyenne group.” And so then you hop into that room and you hop up on our screen in front of us and you’re like, “Hey, Cheyenne, how you doing? What can I help you with?” We have our conversation. You give us what we need, we give you what you need. And then you hang up from this Zoom room and you hop into the next one, which is Provo. And then you can connect with that Provo group from wherever you are. So it’s just a little multiple Zoom breakout rooms in a sense, a good way to visualize that.

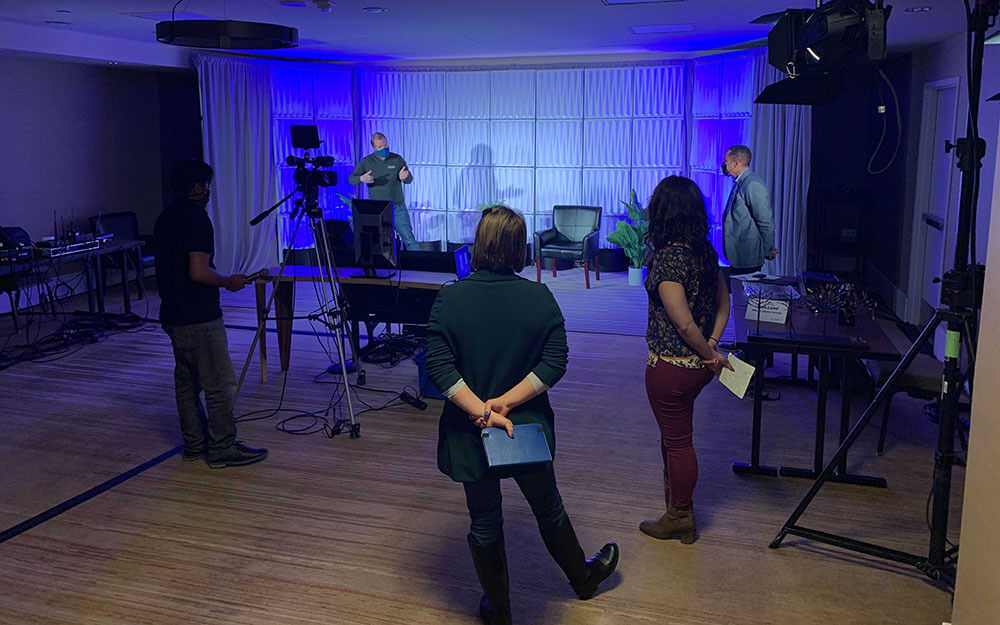

Yurii Land (far right), CMP, strategic account director at Maritz Global Events, hosted R3 from a hybrid studio set up by Encore at the Hilton City Center.

How long did everybody have to work on the problem?

We had about an hour and a half, which is very short for a hackathon. We knew that going into it. We knew that that would potentially be an issue. And this is really one of the tricky parts is, having this be an engaging experience equally across all groups. The virtual span of attention is much shorter than the in-person. We did some prerecorded content to help bridge that gap a little bit better so that people could watch asynchronously, a lot of the stuff that would have otherwise been presented in the hackathon room. And so that helps shorten the amount of time that we need to be together in person, to go easy on the virtual group. And so that helped out a lot.

One of the other issues that we had with going too long was with the hotels. The hotels said we would have to serve more food and beverage if we extended that timeline. We were already asking a lot of our partners, so we wanted to be cognizant of the amount that they’re dropping, because they don’t have the money right now either, nothing is going on. So this planning process was a lot more of going out to the venues and saying, “Hey, what can you do?” instead of Dan going, “Hey, here’s what you’re going to do.” It was a lot more like, “How can you help us?” And so we had to be very sensitive to that. And it narrowed the amount of time that we had available to work with on site.

How many ideas did the judges have to evaluate and how many judges were there?

We ended up with a total of four different pitches and two judges. I think our biggest [piece of feedback] was about the lack in engagement between virtual and the individual locations. The time requirement made that very difficult.

So what would you do differently next time, if you were to hold a similar hybrid event?

For one, communication — setting the expectation before attendees get there and there’s so much to communicate in this environment.

Everything’s at the last minute, you got to do it quickly, watch these asynchronous videos, read all of the things that you need to know before you arrive on site. Oh, by the way, use the chat room in the virtual platform and things like that. We just need more time to be intentional and train folks and really bake it to the experience more. And I think that in the future, maybe we extend the life of the program a little bit in that virtual chat arena because once we get on site and [watch a prerecorded segment], and then you break up into your groups for an hour and a half, you watch a GMID panel, you come back together, get the winners. And then everybody does their little Happy Hour thing.

There’s not much time where they can chat with one another, where the virtual folks can ping somebody individually in Cheyenne or Provo or wherever. That was part of the limitation, was that timing and the format of the program. So I think that expanding the amount of time that we have open to do that stuff, and just the activities that we’re offering.

We did a program in December that was much more successful along those lines but used a different platform. We had availability to do games that were plug-in for this virtual platform. And so that one was much more engaging in that virtual sphere.

And then we did another one, serendipitous celebrations, in March, on a 3D virtual platform. That was really neat. And it felt a little bit closer to being with people because you could actually move around a 3D space and you could see other people walking by and you could see their faces and then you entered into a Zoom. I think one of the things that I would open up is to use some of those other platforms during that pre- and post-event to expand the experience beyond just the event’s virtual platform.

There’s a great part of this hybrid model where you remove the barriers of proximity and you remove the barriers of cost and time to travel. And it’s a huge win for accessibility. It’s a huge win for access to your content — some really major benefits. And one of the reasons that I think that this will stick around, even though it’s hard, is that people are seeing the benefit of that. You just have to shift your approach so that you can engage people in short bursts of time.

The four physical locations for R3, including the Hilton Denver City Center (above), were able to both broadcast to and receive broadcasts from the other locations.

What are other challenges about producing hybrid events that R3 brought to light?

It’s a big investment upfront and it’s a big investment of time along the way. It takes a lot of coordination, much more than it used to. That was a hurdle for us, and I think that a lot of people are going to have that same hurdle. it starts to get costly very quickly — that’s definitely a tough thing that we’re going to have to figure out.

I think there are a bunch of different ways that we’re going to have to look at the business model of events. There’s that technology side. Your cost centers are shifting. During the pandemic, we shifted further away from food and beverage, but as we start to come back and we’re getting more people in-person, that variable cost is going to come back.

The gig economy is such that we’re going to have issues with labor. It took a ton of people to pull this one off. It was far more involved than it would have normally been. We had to have boots on the ground in each of these physical locations. We had to have people who were able to travel or who were local in the area who could be in on the calls and be our on-site meeting planner. All the people it took to pull off all the communication and everything else that went into it, it’s a huge lift.

What are your concerns as the industry recovers?

We’re trying to come back. I don’t know how we’re going to have enough people to pull off the work that needs to be done to bring these events to fruition. It’s a huge resources gap that we’re going to have to address in our industry — that is very real. For example, the [lack of] sales managers at venues, there’s nobody to negotiate with right now. The CSMs aren’t there, the banquet staff isn’t there. A lot of them have left the industry.

That was at the heart of really pushing this hybrid model because hybrid does give you a contingency plan. It’s a way of mitigating that risk and mitigating that uncertainty and with these different venues. But I’d also say that the hybrid model, to do what we did — that lift from one venue to five — that’s not super scalable because of how much extra work it is. But if you can do that, using different venues as things become more relaxed, you actually increase your scalability of your event.

You can adjust those numbers up or down, depending on where we are. So you’re not looking at canceling the event, you’re looking at adjusting numbers. And if something falls through [at one location], you have a virtual component. You just switched it to the multi-modal conference from the design part. And yeah, it’s a lot of work on that design, but once you’ve got it, it buys you so much leverage to adjust according to whatever those needs are. I think that as we go into this continued uncertainty, it gives us a way to go ahead and plan.

Michelle Russell is editor in chief of Convene.