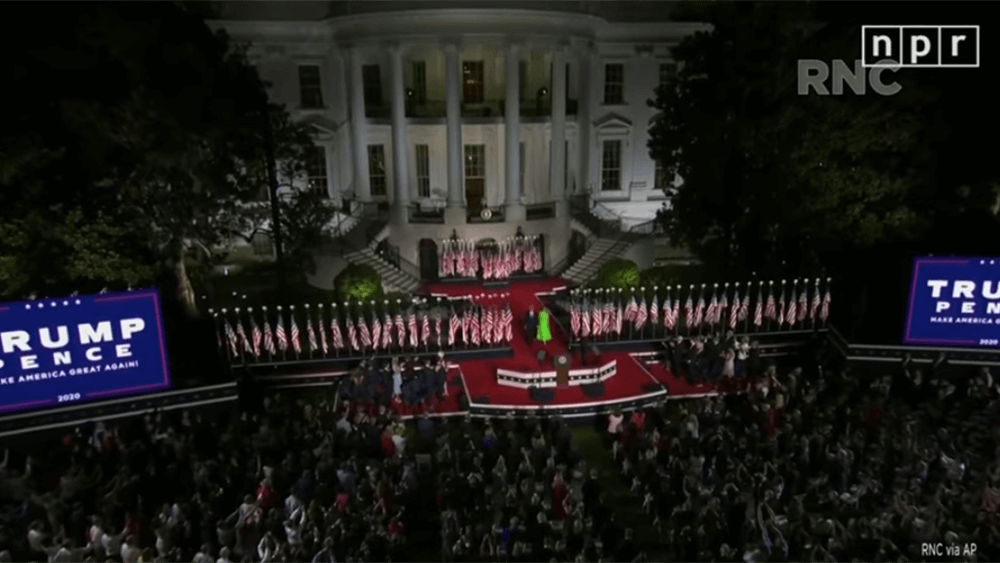

The RNC leveraged the power of place with its controversial use of the South Lawn of the White House for the convention.

The 2020 Republican National Convention (RNC), held Aug. 24 to 27, offered event strategists yet another opportunity to see how the organizers of a high-stakes, big-budget event answer the challenges of capturing audience attention and engagement in the post-COVID world.

Unlike the DNC, held Aug. 17-20, the RNC retained some — greatly scaled-down — elements of an in-person convention. That included convening 336 delegates at the Charlotte Convention Center in Charlotte, North Carolina, for the roll call of delegates and other official business, as well as delivering speeches in front of live outdoor audiences in the White House Rose Garden and the South Lawn.

Here are three non-political takeaways from last week’s event:

1. The power of a place can be leveraged. The RNC made history, and broke convention, when it became the first nominating convention to use the White House as a backdrop. (Many criticized the use of the White House as a violation of the 81-year-old Hatch Act, which prohibits federal employees from engaging in political activities while they are working in an official capacity — a claim that a White House spokesperson rejected.) Politics aside, “the ability to showcase the president in action at the White House and the first lady speaking from the Rose Garden are unparalleled backdrops,” Aaron McLear, the U.S. chair of public affairs for the Edelman public relations firm and a former press secretary to the RNC, told PRWeek. In addition to the White House, the RNC also staged speeches in the marble and limestone-filled Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium, which was designed, according to its website, to reflect the “dignity and power of the Nation,” and Fort McHenry, best known as the site where Francis Scott Key penned the song that would become the national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner.” As both the RNC and DNC have demonstrated, digital events don’t need to be confined to a single location or geographic location. And location can speak volumes.

The speech by Trump campaign advisor Kimberly Guilfoyle seemed “discordant” on a small screen, said author Joe Navarro.

2. Don’t try and replicate live experience — adapt to digital. As we’ve noted before, everyone has a front-row seat at a digital event. So it made little sense for Trump campaign advisor Kimberly Guilfoyle to deliver a speech from a podium in the empty Mellon Auditorium while speaking loudly enough to be heard in the back row. Her tone of voice and expansive gestures may have worked with a live audience, but seemed “discordant” on a small screen, Joe Navarro, author of The Dictionary of Body Language: A Field Guide to Human Behavior wrote in a post-convention analysis for POLITICO. “This manner of presentation is too theatrical. Performances need to meet the audience, and if there’s no audience there, you should shape your performance around that,” Navarro wrote. “Most people don’t remember what politicians say, but we remember the presentation.”

3. Live audiences have an X factor. Many people would — and do — argue that it is not yet safe or wise to hold a live event the size that RNC held on the last night of the convention, when more than 1,500 people, most not wearing masks, packed onto the South Lawn to cheer as President Trump accepted the Republican party’s nomination, followed by a massive fireworks display. The delegates who attended events at the Charlotte Convention Center were required to undergo testing for coronavirus, wear masks, and have their temperatures taken when entering the center; attendees at the outdoor Rose Garden and South Lawn White House events were not all required to be tested for coronavirus or to wear masks.

One takeaway for me, in watching participants determined to participate in RNC events in person in spite of the inconvenience and risk, is that there is something about gathering together that is deeply compelling — and will remain so when we can meet again.

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor at Convene.