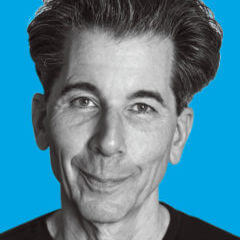

Mark Lipton has served as a leadership adviser to major corporations, start-ups, government agencies, and not-for-profits for more than 40 years. During his time consulting with executives across industries, he noticed more than just a few leaders with angry, aggressive, and downright mean behavior — and they were always men.

Lipton set out to explore whether his personal observations were supported by research, which formed the basis of his recently published book Mean Men: The Perversion of America’s Self-Made Man. Turns out, his experience was the norm: He was hard-pressed to find more than one example of a powerful woman who displayed the same aggressive traits when writing his book.

In an interview with Convene, Lipton said that it’s important to note that much of the most current data on this topic indicates that men and women, on a basic level, experience and process anger in drastically different ways. “Women internalize their anger,” Lipton said, “and men externalize their anger.”

Mean men are somewhat commonplace in business because we’re familiar with such behavior and often even reinforce it, he said. From a young age, boys are told to stop acting “like a girl” and are given permission to be far more aggressive than girls, while girls are reprimanded if they act “unladylike.” These lessons carry over to adulthood — to the point that men are actually rewarded for displaying aggression, and women are judged poorly for doing the same.

“While inherent goodness isn’t gendered,” Lipton wrote in his book, “how we react to and reward the expression of mean traits reflects a gender bias in society.”

Getting Emo Lipton presents in his book research that Victoria Brescoll and Eric Uhlmann, professors at Yale and Northwestern, respectively, conducted about how people perceive inherent

emotions in both genders. Anger and pride were the only emotions people who were surveyed believed that men naturally possess to a greater extent than women — and the expectation that men are therefore more apt to lose their temper would follow.

“When men fly off the handle, they’re regarded more highly than men who do not, who have a very, very even temperament,” Lipton told Convene. An even temperament, he said, is more commonly thought of as a feminine trait.

Women, on the other hand, feel the need to bury negative emotions in order to maintain their peers’ respect. According to Lipton, research shows that women feel anger more intensely and over a longer duration than men but tend to hide it for fear of being perceived as “unladylike.” This can impact their career in big ways, Lipton points out in Mean Men. Experimental research consistently shows that, unlike men, women who try to negotiate for a higher salary are disliked; when they fail to perform altruistic acts that are considered optional for men, they are disliked; and when they are critical of their peers, they are disliked.

“Are the same behaviors that enhance a guy’s status the ones that make a woman less popular?” Lipton asks in Mean Men. “In leadership roles, women may find themselves in a never-ending double bind of figuring out how to direct, command, and control their followers without appearing to do so.”

Stanford University researcher Larissa Tiedens, who is cited in the book, has found that women who express anger often get labeled with a personality-based explanation. “When a woman gets angry in our culture, we immediately associate that with a personality,” Lipton writes. “That’s who she is. She is an angry woman. Whereas a man, he’s merely responding to something going on around him. That’s the perception.”

And while aggressive, angry behavior has been normalized for males, it’s not an effective way to lead, Lipton writes. For more, see the post, “Being Mean Won’t Help You Be a Good Leader.”

Ascent is supported by Visit Seattle and the PCMA Education Foundation.