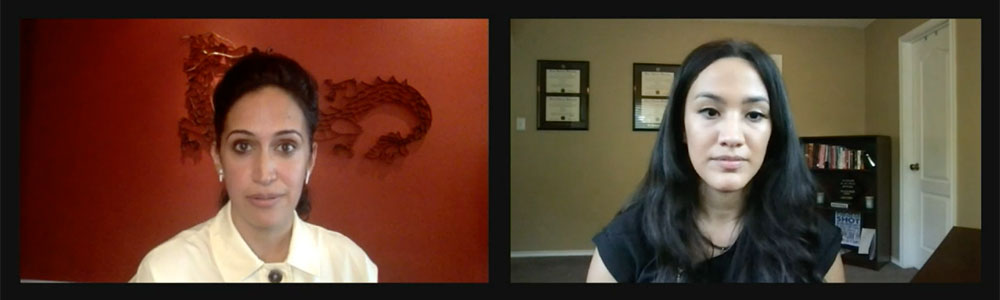

In the first of four videos for “The Gathering Makeover” series, Priya Parker (left) interviews bride-to-be Lisa Torres about the transparency letter show wrote for potential bridesmaids.

In March 2020, Priya Parker, a conflict-resolution facilitator, was working with The New York Times to launch a podcast — to be called “Priya Parker on Gathering” — when a Times producer texted her. “I think it was the first week of March,” Parker recalled last week, during the first of a four-part video series, “The Gathering Makeover,” which she kicked off July 28. “He basically said, ‘We need to put this on pause — a show called “Gathering” is now going to sound like a horror film.’”

But for Parker, author of The Art of Gathering, the questions about gathering in a pandemic were just beginning. In a steady stream of emails, DMs, and phone calls, friends and colleagues were asking: “How do we do this now?” And: “How do we fundraise for our nonprofit, even when we can’t do the gala? How do we galvanize our people, even if they can’t be in the same room?” In April 2020, Parker and the Times launched a 12-part podcast series, “Together Apart,” which looked at how people can meaningfully connect when the ability to meet face to face is restricted.

Now, almost a year-and-a-half later, the context has changed yet again, Parker said last week, as she launched the complimentary “Gathering Makeover” video interviews where she invites a guest to join in conversation about an aspect of gathering and re-emergence. “We are in a collective moment where we each have the opportunity to really make over, one specific gathering at a time, how we want to intentionally convene — and who with.”

The first hour-long talk, which drew more than 1,500 global participants, addressed the topic, “The Power of a Host.” Parker’s guest was Lisa Torres, an auditor from San Antonio, who created a social-media sensation on TikTok in June when Torres described the “transparency letter” she sent to friends outlining her expectations should they accept her invitation to become a bridesmaid at her upcoming wedding. The letter spelled out in detail which events Torres considered mandatory and the approximate expected costs for participants.

Torres wrote the letter, she told Parker, because of her own experience in not knowing what to expect when she had been asked to be in a wedding party. Although Torres received criticism for the letter, much of the feedback — including Parker’s — was positive.

The transparency letter was “to me, this really cool, interesting invention of how you oriented your potential bridesmaids to what it would mean to say ‘yes’ to be a bridesmaid at your wedding,” Parker told Torres. “One of the biggest mistakes we make when we gather is that we assume that the purpose is obvious and shared. And as a conflict-resolution facilitator, I can tell you, when we don’t actually spend time identifying the needs of a group and then bringing people along, a lot of conflict happens.”

Weddings are complex gatherings in which participants bring differing ideas about what will happen, Parker said. But people also come to many different kinds of gatherings — from workshops to board meetings to conferences — with preconceived notions, whether they’re correct or not, she said. “Every gathering has the potential to create a temporary alternative world, where you’re inviting people to bring a specific part of themselves,” she added.

@lisalovesrandom ##stitch with @stephanieberman7 I was scared to have a ##transparency letter in the ##bridesmaidproposalbox but it WORKED OUT. ##wedding ##weddingtiktok

♬ original sound - Lisa 💙

By thinking deeply about the purpose of a gathering and adding a transparency layer by clearly delineating expectations, communications like the one Torres created provide “an on-ramp” that allow people to understand the expectations of the host, Parker said. “The generous host thinks ahead of time about what that temporary world is and how they can communicate expectations in culturally appropriate ways.” Then, “when people come together, they are willing to align with what the expectations are. They have said a true yes.”

There’s another reason to be transparent, and that’s to make gatherings more inclusive, Parker said. The people who are closest to the norm might think letters that spell out expectations are “absurd, or too much.” The people most likely to benefit from clearly defined expectations, however, are those who are decentered, whether for their identity or for economic, language, physical, or other reasons, she said. “They often are the ones who we are equalizing, by making implicit norms explicit.”

“Gathering is about power,” Parker said. “Any time two or more people come together for a purpose … groups have to contend with each other.” Those who organize and host gatherings have authority, she said, but it can be a generous authority.

Barbara Palmer is deputy editor of Convene.

MORE PRIYA PARKER