Condé Nast contributing editor Mark Ellwood tells attendees at the Destinations International Annual Convention that $1.1 trillion is earmarked for airport construction worldwide. The news doesn’t excite climate activists. (Nathan Weber)

When Condé Nast contributing editor Mark Ellwood kicked off the second day of the Destinations International Annual Convention in St. Louis in July, he shared a statistic appealing to business and leisure travelers alike: The world has $1.1 trillion earmarked for airport construction. “We are in an airport boom,” Ellwood said, “like we have never seen before.”

But the prospect of continued investment in an exploding airline industry doesn’t excite everyone — including Greta Thunberg, a 16-year-old environmental activist from Sweden who founded the international school strike for the climate movement last year. Thunberg made headlines at the end of July when she announced plans to sail across the Atlantic to attend the UN Climate Action summit in New York on Sept. 23. For Thunberg, who has used the hashtag “istayontheground” on Twitter in reference to her aversion to the aviation industry’s carbon footprint, sailing was the only transportation option.

“Recently I’ve been invited to speak in places like Panama, New York, San Francisco, Abu Dhabi, Vancouver [and the] British Virgin Islands,” Thunberg tweeted in December. “But sadly, our remaining carbon budget won’t allow any such travels. My generation won’t be able to fly other than for emergencies in a foreseeable future if we are to be the least bit serious about the 1.5 [degree] warming limit.”

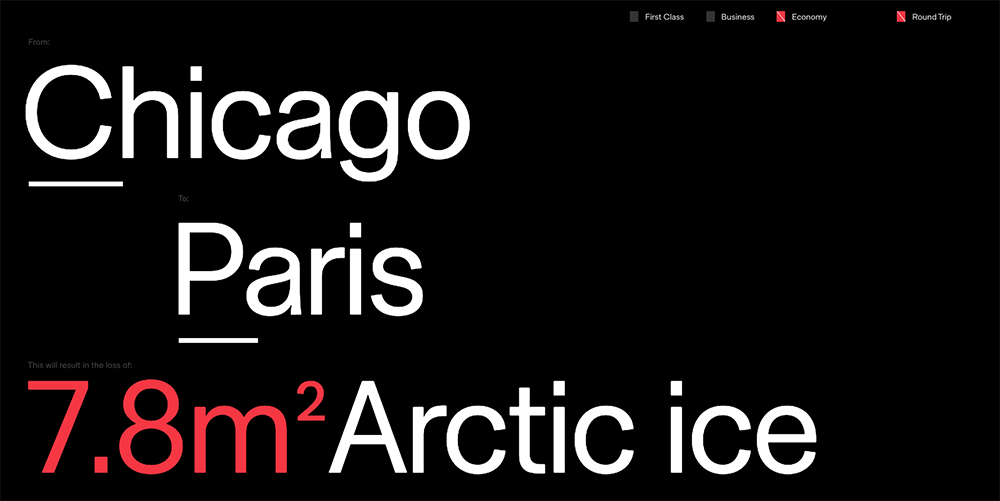

Thunberg is one of the most recognizable voices in a generation that is increasingly concerned about the planet, but she is not alone in her refusal to leave the ground. Two Swedish women have collected 10,000 signatures for a pledge to avoid flying in 2019, and they’re aiming to grow that never-leave-the-ground group to 100,000 people. With new tools like ShamePlane — a website that estimates how much Arctic ice will disappear due to one flight — that goal doesn’t seem unreachable.

On the ShamePlane website, anyone can plug in their airline flight to see an estimate of how much Arctic ice will disappear due to the flight.

Scientists Staying on the Ground

Thunberg’s refusal to take to the skies and her upcoming journey across the ocean, powered by the wind and the sun, is making headlines now, but some scientists and academics grounded themselves years ago. Peter Kalmus, an author and climate scientist from California, launched the website No Fly Climate Sci in 2012 as a place for people — primarily academics and scientists — who either fly less or don’t fly at all in an effort to leave a smaller carbon footprint. “Academics are expected to attend conferences, workshops, and meetings,” reads a statement on the website. “Many academics, including Earth scientists, have large climate footprints dominated by flying. We’re experimenting with having successful and satisfying lives and careers without all the flying.”

Related: Lessons in Hosting a Zero-Emissions Event

The site includes more than 400 members, and in many of their biographies, they focus on the relationship between air travel and conference attendance. “Let’s meet online from now on,” Philipp Gläser, a scientist from Berlin, wrote, “not at over-priced conferences far away.” Ann Pobutsky, a territorial epidemiologist in Guam, wrote that she has “been deliberately not going to annual conferences,” adding that “it is unnecessary to attend these every year when we could all get the information online or via email.”

Airlines Get Serious About Going Green

Carter Yang

There may be more people who prefer to stay on the ground, but that doesn’t mean the skies will be empty. In fact, according to data from the International Air Transport Association, 7.8 billion passengers will travel via plane in 2036, nearly double the number who flew in 2017, and the aviation industry has been taking steps to make that growth sustainable. Carter Yang, managing director, industry communications, Airlines for America, told Convene that U.S carriers transported 42 percent more passengers and cargo in 2018 than in 2000 with only a 3-percent increase in total carbon emissions, and the industry is working toward reducing emissions.

“The world’s airlines, including U.S. carriers, have committed to an international agreement called the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA),” Yang said, “which calls for carbon-neutral growth in international commercial aviation beginning in 2021. We’ve also set a goal of cutting our net carbon emissions in half in 2050 relative to 2005 levels.

“The truth is that the airline industry is helping to lead the fight against climate change with a myriad of measures, including developing sustainable alternative jet fuels and investing in more fuel-efficient aircraft,” Yang added. “In fact, U.S. airlines increased our overall fuel efficiency by 130 percent between 1978 and 2018, saving nearly 5 billion metric tons of CO2 emissions. That’s hardly an environmental record for our airlines or our passengers to be ashamed of. It’s a record of sustainability to be proud of.”

Offsetting Emissions

While all major carriers are taking steps to reduce their carbon footprints, one airline has adopted a surprising philosophy in its eco-conscious approach: Maybe people should think twice before they book flights.

“Do you always have to meet face-to-face?” The question posed by Netherlands-based KLM’s “Fly Responsibly” campaign strikes at the core of the meetings and events industry. It’s a question The Climate Reality Project, which hosted a leadership corps training in Minneapolis Aug. 2–4, proactively addressed in its FAQ section. “Aren’t we producing additional CO2 in the atmosphere by flying out to the training?” was one of the questions listed on the site. The answer, of course, is yes. However, organizers pointed out that they “measure event-related emissions (including air travel) and neutralize those emissions via verifiable carbon offsets.”

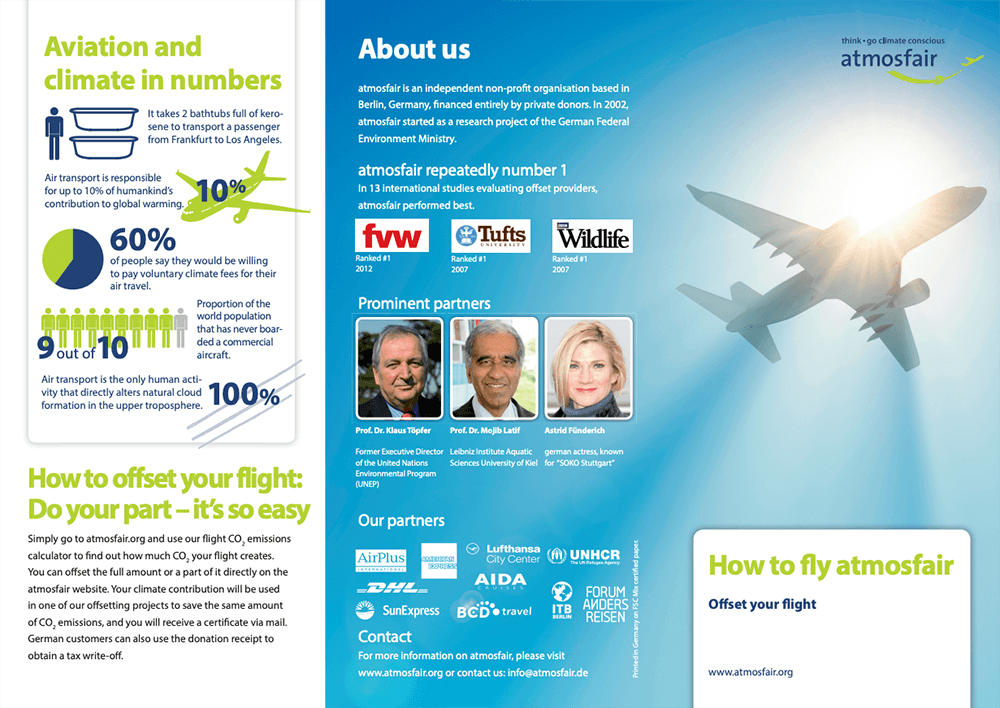

Individual travelers can take the same step to offset their carbon footprint. The German nonprofit atmosfair allows passengers to calculate the approximate amount of carbon emissions they contribute by taking a flight and make a donation to carbon-offset projects — many of which focus on building clean and renewable energy sources in developing parts of the world. In many cases, offsetting the carbon emissions from boarding a plane costs less than checking a bag. For example, offsetting the 426 kg of carbon emissions associated with a round-trip trip from O’Hare to LaGuardia on American Airlines — which I took five times last year — requires a donation of only €10. It’s not as bold as getting on a solar sailboat, but it still counts.

No matter how your attendees get to your next event, you can take steps toward making a more eco-friendly on-site environment. Check out the PCMA webinar “Creating a Sustainable Future for Events” for some helpful tips.

David McMillin is an associate editor at Convene.

The German nonprofit atmosfair allows passengers to calculate the approximate amount of carbon emissions they contribute by taking a flight and make a donation to carbon-offset projects.