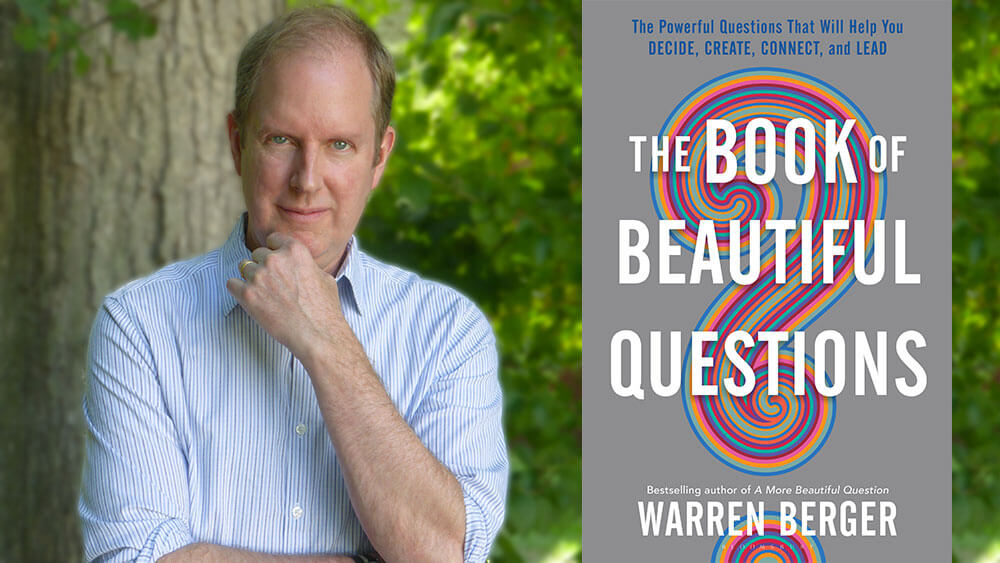

Convene asked Warren Berger, author of the recently published The Book of Beautiful Questions, to talk about how having a questioning mindset makes for a better leader in our January issue. We also asked him to explore how meeting planners can adopt that mindset in their day-to-day work to design more meaningful events. Here’s what he had to say.

Event organizers typically have a pre-con and post-con. I was intrigued with your “pre-mortem” concept, which is a way to approach a new initiative, perhaps one being rolled out at an event. Could you explain how that would work?

It sounds a little uncomfortable to do, but it’s really effective. You basically imagine a worst-case scenario — that the conference didn’t work and that the program you were rolling out was a failure. And what you then try to do is specifically identify or imagine the reasons why it failed — so you’re more or less doing a postmortem in advance. And you’re saying, “The thing failed, and it failed for this reason and it failed for that reason.” That helps you to surface some of the things you should be concerned about, to think about what are some of the things that could go wrong. It gets you to anticipate problems.

A lot of times we don’t do that because when we are rolling out something new, we’re totally in a positive mindset, right? It’s all about, “We love this idea, we’re very excited about it, and we think it’s going to just work like gangbusters. We think it’s going to be great.” That’s good. It’s good to have that attitude. But it’s nice if you can just for a little while, take off the rose-colored glasses and go through one of these kinds of questioning exercises where you say, “Okay, what if it doesn’t work and what would that look like? What might cause that? How would it unfold if this thing didn’t work?” And what that’ll do is it’ll give you some extra things to think about in advance to be on the lookout for.

Related to the process of creating new initiatives at events, in your book you write about lowering the bar when it comes to question-storming, a version of brainstorming. Could you talk about that?

What happens a lot when you’re trying to create something new is you are afraid to move forward until you’ve got what you feel is the perfect idea or a really great expression of that idea. So you feel like something has to be really good before you can put it down on paper, or before you can give it form of any kind, and put it out there into the world. So what happens is, because you’re waiting for this really good thing to emerge before you’ll do anything really with it, it causes people to get sort of paralyzed. They feel like, “I just don’t have a good enough idea yet. We’re just not far enough along with this idea to put anything out there, so we better just keep it to ourselves.” It causes a lot of ideas to never get off the ground.

For an organization that might be thinking about revamping the way they might do an event, they might hold back from taking any action until they had a full plan or until they had something that seemed absolutely bulletproof, before they really put it on paper or create any kind of a prototype for it.

The new way of thinking in the business world, part of the lean startup movement, is the idea that you have to get ideas out there quickly and test them. What you’re looking to do is create the cheapest, easiest way to put an idea out there so other people can see it. You might test it internally or you might find a small group of people you can test it with, but the idea is to get feedback as early as you can. And then you’ll be able to work on the idea, refine it, and make it better.

In your experience speaking at events, what are some of the questions you wish that the event organizers asked you before you sign on the dotted line?

I wish they would ask, “What do you think is the best way to deliver the message we want to deliver or the best way to get the content across?” Because what I would do then is probably get into a conversation with them about the venue, about the way the audience is being set up, or about the length of the program. Lots of things I think should be open to discussion between the people hosting the event and the people who are providing content for the event or the talent. I think too often, what happens when I hear from an organizer, they have a very specific plan of everything. It’s like, “You’re going to come on. You’re going to have 45 minutes. You’re going to have five minutes for Q&A.” In other words, they’ve structured this whole thing without really any input or without really thinking, is this going to be the best way to engage the audience?

Instead, it seems like a lot of times it just goes according to a schedule and a very rigid format. So I would say as much as possible, try to create some flexibility. And get people out of their seats, and whatever you can do to kind of shake up the status quo of events.

You talk about makers versus managers in your book. I think for a lot of event organizers, a great portion of their time is caught up with the logistics of how to ensure everything runs smoothly — which makes them managers rather than makers. What questions should they be asking themselves to help shift them into a more creative maker mode?

One of the key things with the maker versus manager thing that I talked about is how you do your daily work schedule. I got this idea from Paul Graham in Silicon Valley. He talks about how if you are a manager, your schedule consists of all these hourly meetings. Every hour is accounted for, and there’s always a task that has to be done within that half-hour or hour. And that’s the way your entire schedule fills up. If someone is a maker, they have those meetings and things, but they will create a block somewhere in their schedule of a couple of hours that is not about meetings. It’s not about responding to any calls. It’s not about putting out any fires. It’s not about any of that stuff. It’s just about creative time, creative thinking.

What I would recommend is even if you’ve got that kind of a schedule that’s very hectic and that is about checking lots of little boxes, and going to a lot of meetings, and making sure everything gets done, somewhere in there you have to build uninterrupted time, and it has to be a significant block. It might have to be a couple of hours that you dedicate to creative thinking. That might be where you really start to think about the events that you’re working on in very open and new ways. And you allow yourself to explore a lot of ideas, put things on paper, figure out how to do test runs of ideas, that kind of thing.

That period should be very sacred, and you should not allow it to be pushed off the schedule, or interrupted, or any of those things. If you can do that, you’re going to be more creative, because you will give your brain a chance. And you may want to do that with other people.

In addition to coming up with new ideas, event strategists also have to be skilled negotiators. What are some good questions to ask in a negotiating situation?

Negotiating is very much a relationship thing — it’s about building rapport and trust, so how can you ask questions that might create a sense of sharing and trust during the negotiation process? For instance, you might think about using the phrase “How might we” during the course of a negotiation. I think of that as being the phrase that is at the heart of collaborative inquiry, and collaborative inquiry is all about asking questions together. “How might we figure out a way to deal with X or to do a better job at Y?” It’s “How might we figure out a way where you can be happy, and I can be happy? You’re going to get what you need, and I’m going to get what I need, and it’s going to work for both of us.”

You’re trying to find common ground. That’s the way I look at it. Now some people might say, “No it’s about killing the other person. It’s taking advantage of them. It’s about winning at any cost.” That would be very much a Donald Trump approach to negotiation. But my own take is that negotiation is like any other form of relationship building, it’s not about trying to defeat the other person.

Some of the ideas you share in the book for cultivating a culture of questions in an office environment would also work at events, particularly the wonder walls idea — whiteboards where participants could write questions about things that interest them.

Absolutely. Of course, I’m biased. As a questionologist, I think everything should be about questions. But events should be all about the questions. There’s no doubt about it because if you think about what an event is, it’s a time when you step back from the daily routine. And it’s a time when you want yourself to think differently. You want to be more reflective, you want to be more open to ideas. You want to be thinking bigger picture, not just the daily minutiae, right? So an event is really all about questioning. And it will help people to really get more out of the event. A lot of people at work have gotten a little bit shut down. They’re on autopilot. So your challenge at an event is to get them off autopilot. And to make them realize that this is the time to go back to that wide-eyed, creative mindset that they might have had when they first entered your industry. So anything you can do to encourage that kind of curious, questioning mindset — an event is the perfect time to do it.

Learn more at amorebeautifulquestion.com.

Michelle Russell is editor in chief of Convene.